Indonesia CSOs fight “deep fake” elections

The use of AI deep-fakes in Indonesia, during the run-up to this year’s elections, is ringing alarm bells among advocates for information integrity, as they are being used for political gain. As the world watches the country’s fifth direct presidential elections, since the end of the Suharto era in 1998, it is worth taking a look at the struggle to address the downsides of this rapidly developing technology.

Over the past six months, the local and international media have dubbed this the “AI election” and are reporting the mixed concerns and responses of multiple stakeholders to the increasing and controversial use of generative AI by political parties in their campaigns.

A number of AI-generated audio and video clips have surfaced and gone viral on social media between October 2023 and January this year, mainly targeting presidential candidates.

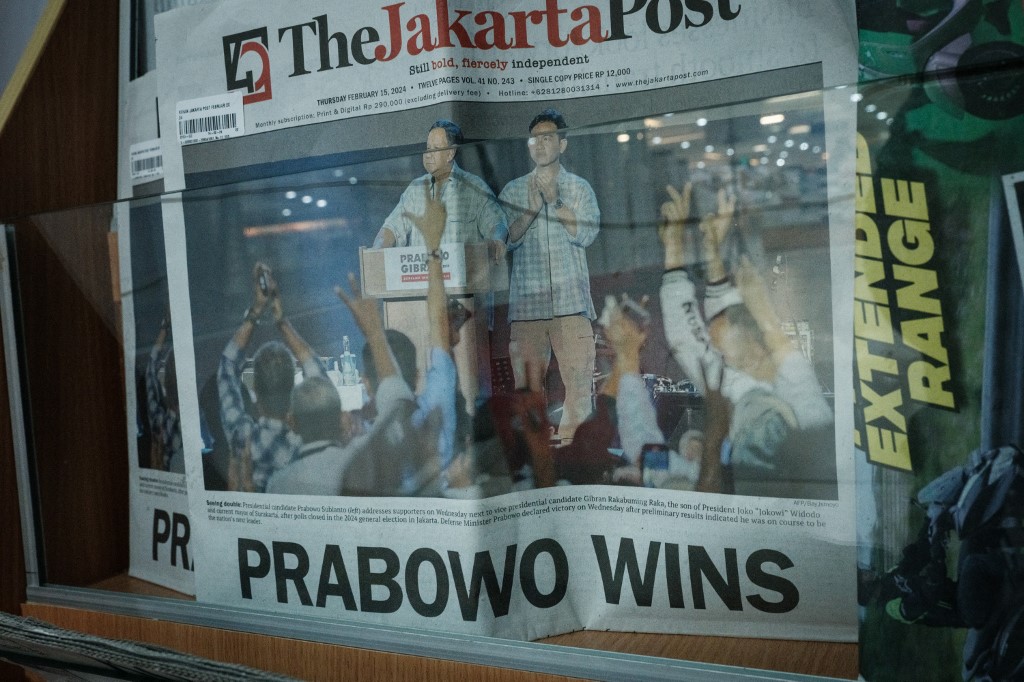

One was an AI-generated clip resurrecting the late President Suharto, apparently asking voters to support presidential frontrunner and current Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto, behind whom the Golkar party, founded by Suharto, is throwing its support. Others include Prabowo’s “warm and cuddly” personality makeovers, in an attempt to soften his stern image in his neo-nationalist Gerindra party’s political campaigns.

Following a public outcry, both campaign teams defended the two AI-generated makeovers as being harmless and for not attacking other candidates, which is an offense under the country’s 2017 elections law.

Another audio-visual deep fake surfaced on YouTube in October last year, purportedly to be incumbent President Joko Widodo speaking Mandarin, presumably to stoke fire on his critics about Indonesia’s cozy ties with China. In fact, the original video was of a speech he gave in English at a dinner party during his 2015 visit to the United States.

Another presidential candidate and former Education Minister, Anies Baswedan, has become the latest victim of an audio deep fake, when a conversation between him and his political mentor surfaced online in late January. It purported to be a recording of Anies being reprimanded for his underperformance and lacklustre campaign, with the obvious intent to damage his standing in the elections.

After several such incidents, the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology issued advisories for tech firms developing AI tools and advised voters to be aware of the potential dangers of deep fakes. This may, however, be too little too late, because these clips had already reached millions of social media users before being taken down.

There are also countless manipulated and manipulative images being widely used by legislative candidates to attract voters and OpenAI-powered interactive chat bots are used by main political parties to reach out to potential voters and interact with them about the party’s policies.

While it could be argued by some that there have been many beneficial applications for AI technology, which have increased citizen participation and strengthened democratisation in previous elections in AI-literate countries, such as India, France and New Zealand, one cannot help but wonder where exactly the legitimacy in this AI electioneering lies.

In the Indonesian context, where the political leadership drums up the potential of AI for the economy to woo voters, the use of AI deep fakes to manipulate voters has become quasi acceptable, as long as it is used in a positive way and labelled clearly as being AI-generated content.

This argument could, however, set a bad precedent for other countries with elections this year to follow and may, inadvertently, earn the beneficial use of AI tools, such as in facilitating the election process, including election data management, analysis, vote counting and validation, a bad name.

While there are weak standards related to online trust and safety and internet governance policies held by governments around the world, fake and manipulative propaganda and influence operations which cause harm incite hate and trigger violence and are prohibited, particularly when their intent is to trick or micro-target voters to the benefit of their political party and candidates.

Until recently, Indonesia has been a positive example of a functioning democracy in Asia, with a healthy set of checks and balances and vibrant civil society, which often fights to set a high bar in defending democracy and human rights.

More so, its earnest and rigorous response to the threat and challenge brought on by the prevalence of disinformation and hate speech, particularly state-related disinformation campaigns, is a shining example for other ASEAN countries.

Indonesia could do well to learn lessons from prior elections in other ASEAN member states, such as the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand. There, social media users are able to see how established powers leverage their upper hand in controlling technology, lawfare aside, to stay in power, at the expense of democracy.

Their political leaders, instead, got the wrong side of the Philippines’s internet-savvy society. We see state actors attempting to harness the potential of the online space to rectify the country’s autocratic past, effectively re-writing history to attract young voters. Indonesia has over 200 million eligible voters, many of whom had not even been born when the country was under Suharto’s 32-year rule.

Nonetheless, Indonesia’s civil society remains robust and strong. To name one good example, it took them only a few months to get all 18 contending political parties, three presidential and vice-presidential candidacy teams, the Election Supervisory Agency (Bawaslu) and partners in civil society to sign up to a voluntary framework on social media use in political campaigns to protect election integrity on January 21.

The agreement, which is, in part, modelled on Thailand’s Code of Conduct on social media use in political campaigns, was signed by 36 political parties ahead of last May’s general election. It commits the signatories to non-violent and fact-based online campaigns and information transparency, among other things.

While this framework, crafted and facilitated by the Switzerland-based Henry Dunant Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD), is not legally binding and follows serious AI deep fake incidents, it is a significant step in the right direction.

In Thailand’s case, this initiative provides watchdog groups with a monitoring framework, to track and investigate any harmful and manipulative online behaviour by political parties, candidates, supporters and individuals during the elections. This informs effective intervention and policy formulation in defence of election integrity.

After all, the diverse ASEAN rights-based community should stick together and learn from each other. Empowering citizens with AI, digital literacy and the competence to hold the governments to account should be part of a resolute fight to safeguard democracy.

Kulachada Chaipipat is Thailand-based media consultant and advisor to Cofact Thailand. She has contributed this article to Thai PBS World.