Thailand agonizes over fate of hunger strikers — and lese majeste law

In an almost unprecedented move, the House of Representatives convened last Thursday (Feb 2) to debate possible measures to save the lives of two young activists on hunger strike.

On January 16, Tantawan “Tawan” Tuatulanon and Orawan “Bam” Phuphong poured red liquid over their heads in a symbolic protest in front of the Criminal Court in Bangkok, then asked the court to revoke their bail. The two young women are charged with insulting the royal family, under the so-called lese majeste law.

Two days later, the duo began a hunger strike to protest against what they call unjust pretrial detention of those who criticize the Thai monarchy.

They also made three demands for reform of the justice system: an end to the prosecution of people for exercising freedom of expression, and repeal of the lese majeste law, or Article 112, and of the sedition law, Article 116. Lese majeste is punishable by up to 15 years in jail under Article 112 while Article 116 carries up to seven years imprisonment.

Who are Bam and Tawan?

Orawan, 23, described herself as an independent activist who has joined anti-government protests regularly since 2020. In August last year, she took part in a rally demanding the removal of electronic monitoring (EM) bracelets from all political activists released on bail. She said she lost her job after being forced to wear one.

She was arrested on February 8 last year after joining Tantawan to conduct a public opinion poll on royal motorcades at a busy Bangkok shopping mall.

Tantawan, 21, was a guard of the We Volunteer (WeVo) group of young anti-establishment protesters. She was arrested on March 5, 2022, while broadcasting live on Facebook as a royal motorcade was passing protesters in front of the United Nations building in Bangkok. While in detention, she staged a hunger strike for 37 days before being released on bail in May last year.

The pair were initially denied bail, before it was granted with conditions, in line with the treatment of other protesters facing similar charges. Under bail conditions, they were forced to wear EM bracelets and prohibited from taking part in political protests.

But both opted to request revocation of their temporary release, in solidarity with fellow activists denied bail after being charged with lèse majesté and other offences stemming from their political activism. The Criminal Court granted their request, and the two women were remanded at the Central Women’s Correctional Institution.

Courts usually only cancel bail as punishment for defendants who breach their conditions of temporary release while awaiting trial.

Concern for health grows

After three days of hunger strike, both activists were moved to a hospital inside the prison compound, although they refused medical treatment.

On January 24, their condition deteriorated further after seven days without food or water, and they were transferred from the prison’s medical facility to Thammasat University Hospital in Pathum Thani province. The hospital reported on Saturday that the pair continued to refuse food although they had started sipping water. They were suffering dangerously low blood-sugar levels as well as mineral deficiency, with abnormally high acidity of the blood.

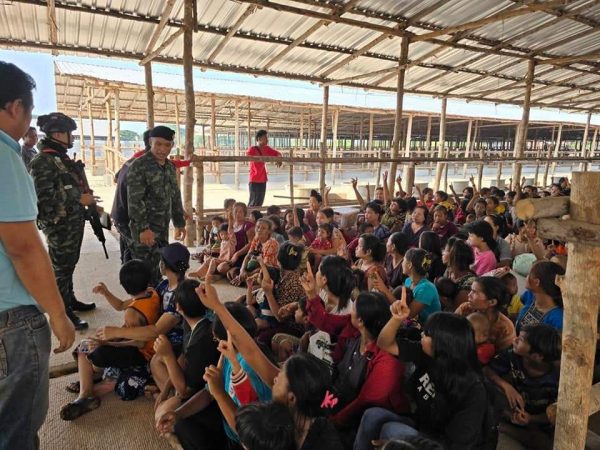

Small demonstrations in support of the pair and fellow detained activists were held at different locations in the city. These included the “Stand Against Detention” event held outside the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre.

Call for end of hunger strike

Activists and opposition politicians voiced support for Bam and Tawan as they continued to refuse food. Many people, though – government critics and supporters alike, as well as a Buddhist monk – pleaded with the pair to end their protest immediately as concern grew over their worsening health condition.

On January 26, six opposition parties issued a joint statement calling for authorities to seek views from all relevant parties about judicial reform. They also called for defendants’ rights to temporary release to be considered “in a fair manner”.

However, opposition parties led by Pheu Thai and Move Forward stopped short of addressing the third demand by the hunger-striking activists – removing the lèse majesté and sedition clauses from the Criminal Code.

Critics say the main opposition parties likely fear taking any radical stance that might alienate conservative voters and damage their chances the general election tentatively scheduled for May 7.

Political pawns?

Last Wednesday (Feb 1), Pheu Thai and Move Forward submitted an urgent motion for a House debate to propose measures that could be implemented by the government to save the lives of two hunger-striking activists. But the debate on the following day saw government and opposition politicians accuse each other of using the pair as pawns for political gain.

Pheu Thai leader Cholnan Srikaew said the activists’ third demand was “a matter for the future” that should be dealt with by all political parties in Parliament. He said any law with flaws needed to be amended, though did not specifically mention the articles on lese majeste and sedition in the Criminal Code.

Cholnan, who is opposition leader, said that the powers-that-be’s failure to act over the activists’ worsening health was tantamount to an attempt to cling to power.

MP Ongart Klampaiboon, deputy leader of the coalition Democrat Party, said his party disagreed with the abolition of the lèse majesté law but would not oppose any House motion to do so.

However, he stressed that “nobody should seek to make political gains from this hunger strike”.

By Thai PBS World’s Political Desk